by Wendy Chang

The Oxford Dictionary defines quality assurance as ‘the maintenance of a desired level of quality in a service or product, especially by means of attention to every stage of the process of delivery or production’. In evaluating the quality of a service or product, client satisfaction with the service or product is often used as a measure. In the higher education context, quality assurance is also often used interchangeably with quality management.

With a lack of consensus on the definition of quality, product and client in the higher education sector, assuring quality in higher education is easier said than done. For example, are the academic programmes offered by a higher education institution the product, or are the students or graduates its product? Is the student who pay fees a client, or the funding entity that sponsors the students’ education, or is the industry that employs the graduate the ultimate client?

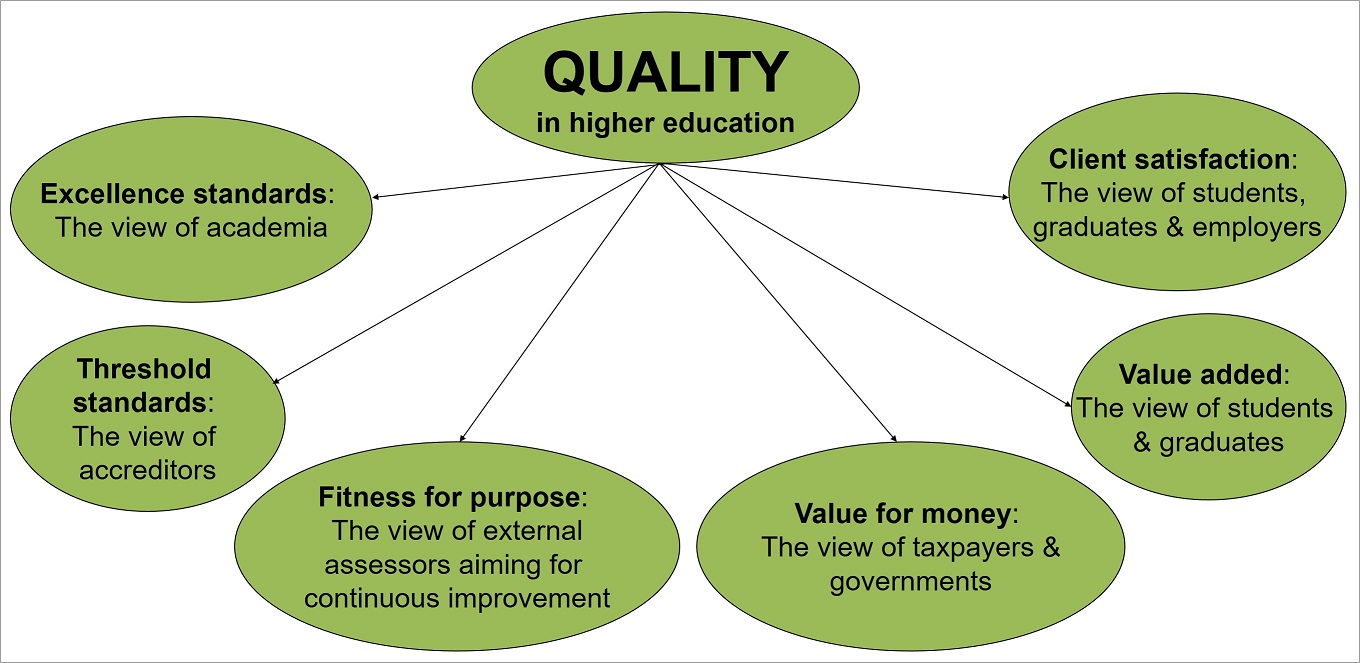

Highly regarded authors of quality in higher education, Diana Green, Peter Knight and Lee Harvey, provided a comprehensive definition of quality in the 1990s: “First, quality means different things to different people. Second, quality is relative to processes or outcomes“. The ASEAN University Network (AUN) has also adopted this multi-stakeholder view of quality when it developed a manual for the implementation of the AUN Quality Assurance (AUN-QA) Guidelines. Figure 1 summarises the multi-stakeholder view of quality. Thus, a higher education institution essentially has multi-clients and multi-products.

Figure 1: Multi-stakeholder view of quality (Source: Green, D. What is Quality in Higher Education? Concepts, Policy and Practice 1994, cited in ASEAN Universities Network – Quality Assurance (AUN-QA)’s Manual for the implementation of the AUN-QA Guidelines, 2005)

Authors on quality management in higher education from Australia, Srikanthan and Dalrymple (2007) recognised the uniqueness of the higher education sector in that it provides not only administrative services similar to those in other service industries but also professional teaching, research and consultancy services that transform students into human resource that develop countries and drive the global economy. They reasoned that a holistic model for quality management is necessary to meet the various stakeholder expectations.

The holistic model reflects extant literature on the multi-stakeholder view of quality in higher education and Article 11 of the World Declaration on Higher Education for the Twenty First Century: Vision and Action adopted by the UNESCO’s World Conference on Higher Education in October 1998.

Article 11 highlighted that ‘quality in higher education is a multi-dimensional concept, which should embrace all its functions, and activities: teaching and academic programmes, research and scholarship, staffing, students, buildings, facilities, equipment, services to the community and the academic environment…Due attention should be paid to specific institutional, national and regional contexts in order to take into account diversity and to avoid uniformity… Quality also requires that higher education should be characterised by its international dimension: exchange of knowledge, interactive networking, mobility of teachers and students, and international research projects, while taking into account the national cultural values and circumstances.’

In today’s environment of high student and graduate mobility as well as international business networks and opportunities, a holistic model suggests taking on the perspective of quality assurance or management with a purpose shared by the multi-stakeholders to produce graduates who are ready to participate and contribute to the society locally and globally.

At the national level, Prime Minister Tun Dr Mahathir Mohamad has highlighted that there is a mismatch between education and the industry demands. Although Malaysia has an overall unemployment rate of 3.3% (considered by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development considers as having ‘full employment’), youth unemployment rate is relatively high at 10.9%.

In July 2019, Tun Dr Mahathir specified that other than graduates’ poor attitude towards employment, the lack of skills, education and work experience as well as skills mismatch are among the contributing factors of unemployment among the youth (defined as those between 15 and 24 years of age). Reducing the national youth unemployment rate should be an immediate shared purpose of quality assurance in the Malaysian higher education sector.

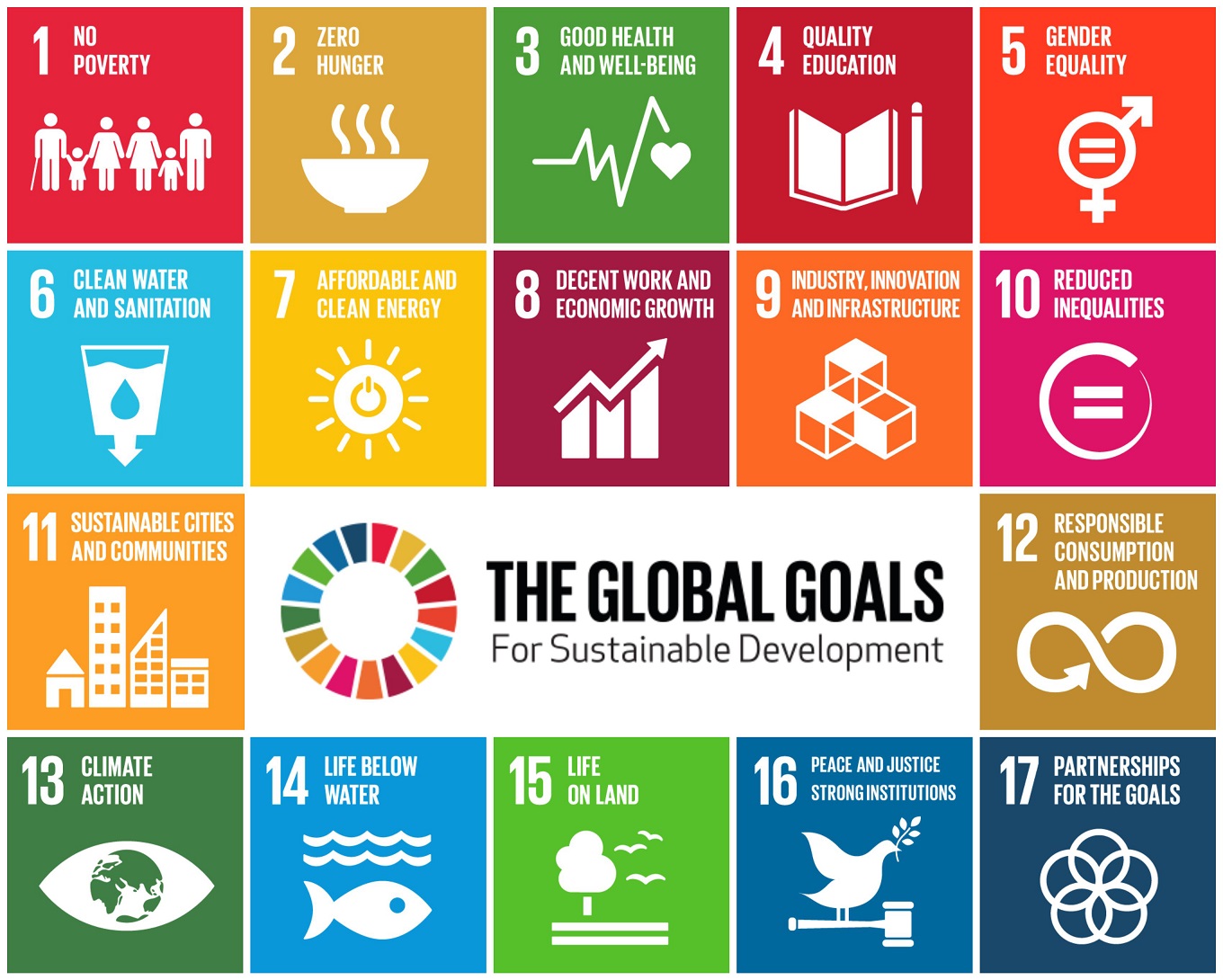

Quality assurance or management could also have a shared purpose at the regional level. The ASEAN Qualification Reference Framework published in 2014 and the Malaysian AQRF Referencing Report endorsed in May 2019 facilitate student and graduate mobility to enhance the exchange of culture, knowledge, skills, innovation and networks to promote regional peace, stability and economic growth. Ultimately, quality assurance in higher education can seek global shared purposes in the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals as summarised in Figure 2.

Figure 2: United Nation’s 17 SDGs (Source: UN 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, 2015)

Quality assurance with a shared purpose requires visionary leadership as well as longer term managerial thinking and planning to find the balance of satisfying all the stakeholders of the higher education sector. Through holistic quality assurance in higher education with shared purposes that serve all stakeholders of the sector, higher education institutions have the power to ensure that the necessary steps are taken now to sustain the development of a better world. The seed of transformation for a better world lies in hands of the higher education sector.

Wendy Chang is a senior lecturer from the Faculty of Business, Design and Arts at Swinburne University of Technology, Sarawak Campus. She can be reached via email at Wchang@swinburne.edu.my.